Carl Martin had a front-row seat to one of college basketball’s most infamous eras. Carl, the son of Ed Martin, the former booster whose payments to Chris Webber and other members of the Fab Five — led to one of the most high-profile investigations in NCAA history, chronicles his father’s life in his new book, “The Booster: How Ed Martin, The Fab Five and the Ballers from the ‘hood Exposed the Hypocrisy of a Billion-Dollar Industry.” Carl spent 15 months in the federal prison system rather than testifying against his dad about the illegal numbers operations they were both involved in. This excerpt of the book, which goes on sale Monday, was provided to the Free Press for special publication:

Time may heal wounds but it has not diminished the notoriety of the University of Michigan’s Fab Five. The aura surrounding that iconic quintet eclipses the individual members of college basketball’s most famous recruiting class.

Even casual sports fans know the CliffsNotes version: When five high school All-American superstars join forces in Ann Arbor, they become the richest freshman haul in NCAA hoops history.

The quintet:

Ray Jackson, the quiet-but-stellar Texas shooting guard seemingly content to ply his game in the shadow of his better-known teammates.

Juwan Howard, the easy-striding, 6-foot-10 Chicagoan as capable of high-octane offense in the low post as he was of straightjacket-style defense.

Jimmy King, gap-toothed, quick-tempered, a guard/small forward possessed of a superhuman vertical leap and an appetite for a defender to posterize.

Jalen Rose, the charismatic point guard whose defensive relentlessness and fearless offensive forays into the lane embodied a hood-hardened style forged as much from Perry Watson’s demanding practices as from Detroit’s rugged streets.

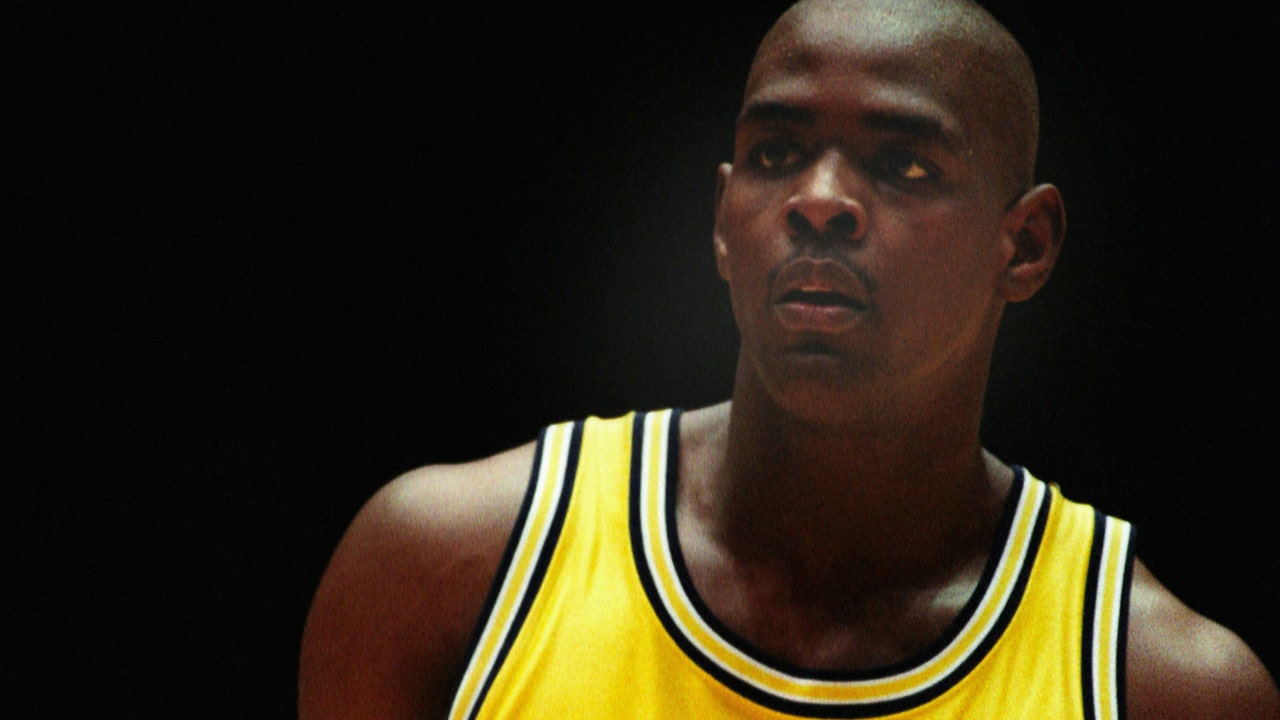

Chris Webber, the 6-foot-10, 245-pound center/power forward, the Hall of Famer in-waiting, a middle-class man-child whose size, athleticism and intellect coalesced to turn him into arguably the single best college basketball player of his time.

These five young, African-American, hip-hop-flavored freshmen were unleashed on an unsuspecting basketball world. They would leave the game drastically different from the way they found it.

More Fab Five:

Michigan’s John Beilein still hopes to embrace entire Fab Five

Chris Webber’s Fab Five legacy complicated — time to end the timeout

As a quintet, they were together only two years, but that was all the time they needed to refashion the college hoops landscape. The products of big-city blacktops from throughout the Midwest and Southwest, they injected a decidedly black and urban flavor to the game. They featured trash talk, dramatic hand gestures and gleaming bald heads and put it on display in a Midwestern university campus that prided itself on tradition with more than a touch of elitism.

By becoming NCAA championship finalists as both freshmen and sophomores, the Fab Five obliterated the age-old basketball gospel that a team can’t win with five newcomer starters. And with their baggy shorts and black socks, they revolutionized basketball’s

dress code. Overnight they reduced snug uniforms to laughable fashion relics.

Of course, the college basketball world had been transformed into a multi-billion-dollar cash machine long before King, Rose, Jackson, Webber and Howard ever took to a court together. Nevertheless, the impact of the prized quintet penetrated deep into the NCAA’s bottom line. It took merely one game for the collegiate sports industry to recognize just how lucrative the Fab Five could become.

Driven by the national obsession of postseason “March Madness,” the NCAA’s basketball revenue had been climbing steadily in the years prior to the Fab Five’s arrival. By the time Chris and Co. played their first game, the money generated by collegiate basketball had exploded beyond what anyone could have anticipated.

The Fab Five’s first year, 1991, also marked the beginning of a seven-year, $1 billion mega-deal between CBS and the NCAA that gave the network the rights to broadcast every game in the tournament. The agreement, announced in 1989, poured nearly

$143 million a year into the NCAA’s coffers — nearly triple the size of the previous contract. The NCAA’s own magazine, Champion, described the deal as “stunning” and a “game-changer.”

Just as significant was the fact that 1991 also marked the start of a new compensation system for tournament entrants that found each college or university earning more money for each postseason victory. By 1995, with college hoops now in the midst of a TV ratings explosion, the NCAA and CBS were negotiating a contract extension through the 2002 tournament that was worth $1.725 billion.

That was followed by an 11-year, $6 billion deal. But even as the NCAA, academic institutions, TV networks and apparel manufacturers were setting up to earn billions, the players — including the Fab Five — were learning a harsh lesson about who wasn’t eligible for a cut of the windfall profits basketball was generating.

Everyone was getting a juicy slice of a big pie — everyone but the players.

Even as freshmen in 1991, they may have been young, but they were nothing if not street smart. Each of them knew what it was like to be coveted, to have seemingly mature adults swoon over them. Their rare gifts on the hardwood sparked outlandish promises even as their intimidating bald heads and black game socks took off in popularity. Jimmy King says the look was the Fab Five’s nod to the Black Power sentiment that infused hip-hop culture during that period. Young but not naive, they understood the attention, power and revenue their brand could generate. But they also were painfully aware of how the same NCAA system that used their talents to turn athletic directors and TV execs into millionaires ensured that they could never receive a dime of those riches.

It was into that atmosphere that Webber and Rose hit campus. By that time, Ed Martin’s relationship with them and with Detroit prep basketball had changed significantly. The last few players who kept Ed tethered to Southwestern had left or would soon be gone.

Howard Eisley went to Boston College in 1990. Voshon Lenard earned a scholarship to the University of Minnesota in 1991. That same year, Coach Watson left his throne atop the prep basketball world to join Steve Fisher’s coaching staff. In just two years, Southwestern High School lost much of its standout talent, as well as bidding goodbye to Coach P. Watt, the architect behind the program’s decade of dominance.

My father, too, was moving on. Although he always had maintained ties to other great players around metro Detroit and the state, his friendship with the Webbers represented the first time he’d ever devoted significant attention to a non-Southwestern player.

And now that Detroit’s greatest high-school basketball program ever was ending its run, Big Ed began to consider branching out. The problem wasn’t just that the run was over, though. For my dad and Coach Watson, the end of the Prospectors’ era also signified

the end of what once promised to be a lifelong friendship.

In his early days on the fringes of the program, my father had been content to care for the players Watson had already assembled. But that role had elevated considerably from delivering Gatorade and snacks and taking the team out for meals.

He had steadily taken a more active role in the life of certain players. He talked with them about the colleges they were considering, which coaches would do best by them, which teams seemed most suited to their styles of play. And it was there that Ed Martin ran afoul of Perry Watson.

No player’s situation illustrated that clash better than Howard Eisley’s. Following his stellar junior season in 1989, in which he helped lead Southwestern to yet another state finals appearance, Eisley became a coveted recruiting prospect. Teams across the country were reaching out to Watson for an opportunity to sign his point guard to a scholarship. However, Watson had close ties to the Kent State program and made it clear to Eisley that he thought the Ohio school would be best for him.

Eisley wasn’t so sure. Kent State was a Mid-American Conference (MAC) school, and he felt certain he wouldn’t get as much exposure as if he went to play ball in, say, the Big Ten, Atlantic Coast Conference or Pac-12. As one of three main cogs, along with Jalen Rose and Voshon Lenard, on the team that won Watson his first state title, Eisley felt he had the potential to showcase a much higher profile than the MAC could provide.

Against his coach’s wishes, he began considering other options. Ed Martin encouraged Eisley to look further afield. Tony Jones, a former assistant coach to Watson at Southwestern, convinced a friend at Boston College that Howard was the point guard they needed. After watching him in one playoff game, the friend agreed.

Eisley was understandably conflicted over which school or conference would be his best option. He decided to discuss his dilemma one more time with Watson — and also with Ed Martin. When he asked Ed’s advice, the answer was unequivocal. Go East, young man, where your odds of making it to the NBA will be far better.

While Watson wasn’t thrilled with Eisley’s decision, he ultimately accepted it and continued to counsel and support his former player, even after he went off to Boston. But that incident changed Watson’s perception of my father.

Ed was still his friend and still a friend to the program. But Watson was now slightly wary of a man who was increasingly carving out an expanding role for himself. As long as Ed’s influence was limited to the locker room or the bleachers, all was fine. But this excursion into recruiting and player development drove a wedge and the two began to grow apart.

Years earlier, Ed had made it clear to Watson that he was backing Webber, even at Country Day. Now, by giving counsel to Eisley, for the first time, Ed’s loyalties were divided. Clearly, his ambitions were much bigger than the Southwestern program. He had already shown in his support of Chris Webber that Big Ed Martin could take his money and his support anywhere he wanted. By attaching himself to Webber’s star, he left no doubt he was more than willing to do just that.

The decision was unspoken: Ed wasn’t abandoning Southwestern, but he had chosen his relationship with Webber over maintaining warm ties with Watson. Although Ed continued to hover around the Prospectors’ program during Watson’s final year there, it was apparent to me — even if it wasn’t to the players — that P. Watt and Uncle Ed Martin were no longer the friends they’d once been.

The bond snapped totally and irreparably when Watson decided to leave Southwestern to join Rose and Webber at U-M. He had been cool with what Ed had done as long as it helped his Prospectors’ program. Now that he was going to Michigan, Watson seemed to have decided he couldn’t afford to be associated with Ed because he knew he couldn’t control Ed’s expenditures. A man who had aspirations of being a head coach at a major college couldn’t risk the taint of an NCAA scandal. So the legendary high

school coach stopped talking to Big Ed Martin.

For his part, my father still cared about Watson. That was not unusual because he didn’t walk away without good cause from a relationship. But he realized that Watson wanted to distance himself from him and he understood why.

My mom had a different opinion of Perry, but then, she had always been leery of many of the people my dad was close to. She saw Perry as one of the many who took advantage of her husband. Mom would constantly remind Dad about all he did for Watson while the coach never did anything in return. Ed would shrug it off. Watson was a Detroit public school teacher and basketball coach. Of course he didn’t have a lot of money.

Hilda Martin didn’t see it that way. She felt Watson didn’t even show appreciation. “It doesn’t cost much to prepare somebody a chicken dinner,” she used to say.

Even though Watson was now at Michigan, Ed didn’t need his friendship to operate there. He already was close to those at U-M who were most important: the players. The way he put it:

“Sometimes I gave gifts to parents: cologne, cakes, a few dollars here or there, something like that. I gave a cake to Roy Marble when I went to Flint. And Terence Green, when he was a big star up at Flint, I left him a sweater. Marble, I bought him a sweater, too. Well, that wasn’t for Southwestern. That was helping Michigan out.

I was trying to recruit for them, but his father decided he didn’t want Michigan to take him.

“But I would give, and they knew that I would give to anybody. To Callahan’s mother and father, to Hunt’s mother and father, I took them stuff all the time. Perry’s mother and father, I took them dinner, I used to buy 15 dinners and take them to the whole basketball team.

“I bought stuff for Chris, Jalen, other people. I had all kind of stuff made. And they were happy. It was just something I did for kids.”

Watson, Rose and Webber had taken a leap to the next level. And so had Big Ed Martin.

His “godson” was now the star attraction for one of the nation’s most storied universities. Chris Webber and Jalen Rose were the most can’t-miss pro prospects Ed had ever seen. These two kids who had dominated middle-school ball as the Superfriends were now captivating the college hoops world. It was all but a sure thing they would cash in, big time.

No longer was Ed bound by Perry Watson and his strict rules. And with Rose and Webber ensconced at U-M, Ed could do as he pleased. Maybe he didn’t see it that way at the time, but his insistence on maintaining a relationship with Webber after he had chosen Country Day over Southwestern had been Ed Martin’s declaration

of independence from Perry Watson and the Prospectors.

Dad would always harbor fond memories of the program and of the many youngsters he helped at Southwestern. Now he could “help out” talented players on an even grander scale.

Before Webber, Rose, Eisley or Lenard, the closest Ed had come to seeing one of his kids make it big was Antoine Joubert and Tarence Wheeler. But they were performing only in overseas leagues.

Now, Ed had ties to guys with more than just a measure of pro potential. Suddenly, he had gone from rubbing elbows after high school games with superstars

to riding in the orbit of potential Hall of Fame greatness. Even before their images skyrocketed as the most visible members of the Fab Five, Rose and Webber were projected as sure-fire NBA lottery picks. Lenard was also enjoying a standout college career, as was Eisely, who left the year before. All were being hailed as potential high-round NBA draft picks.

Ed was self-aware enough to know he couldn’t be an agent or financial manager. For all his math prowess, he was still only a factory electrician. That didn’t stop him from entertaining dreams of the NBA glory “his boys” would achieve and musing about ways he could be involved.

Maybe he wouldn’t be anything more than a personal advisor or a board member on one of the players’ charities. Maybe he’d just be good old Uncle Ed, whose charity would be fondly recalled at holidays. Perhaps one of them would fund a scholarship in his name.

Dad didn’t care where his seat was in the inner circle of the future pros he helped nurture. He just wanted to belong. With no P. Watt to rein him in, Ed grew bolder with his giving and spread his money around even wider.

When word got back to him that Voshon Lenard, then in his sophomore season at Minnesota, was struggling to brave the bitter Minneapolis winters without a heavy coat, Ed immediately had one shipped to Minneapolis. It was not some inconspicuous down jacket, but a full-length leather coat with a fur hood. Let the kid cut

a figure.

The Webbers may have benefited the most from Ed’s largesse, but they weren’t the only ones associated with the Maize and Blue who received his help. Rose got more than a few dollars under the table — during his time at Southwestern and at Michigan.

“Ed helped them both out a lot, but Jalen was always cooler about his, always had other places he could turn to other than Ed,” recalled Fred Lamar, a high-school friend of Rose’s who later became an integral part of Webber’s entourage during the Fab Five era. “Jalen had come out of Southwestern, so he knew how he was supposed to deal with Ed. He loved Ed just like the other Southwestern guys did, so with him there wasn’t any trying to use Ed or trying to get over on him.

“Jalen went to Ed with what he needed. Ed would do anything for Jay or Chris, and he was always making sure they had a couple of dollars in their pockets. But Jalen always made sure that he only went to Ed when he didn’t have any other choice. Chris was living off of Ed.”

Though Webber and Rose maintained the closest ties to Ed, it didn’t take long before Big Ed had won over every one of the Fab Five. Ed was nowhere near the benefactor to King, Jackson or Howard that he was to Rose and Webber, but he did his best to spread at least a little cash around the locker room. Even today, former teammates of Webber and Rose look back fondly on Ed.

“Ed was just a good person,” King said. “When you come into the school, people from the area want to connect you with people who can help you and people that need to be a mentor or should be a mentor. We were meeting a whole bunch of people. I was meeting people in Ann Arbor, people out of Lansing, people in Detroit. I was meeting people everywhere, and he was a good guy to me.

“The first time I actually spent time with him was when we were in Ann Arbor. He invited us to his home. It was early in our freshman year, like in the fall, a couple of months into school. We had been on campus for a little bit. I think all five of us went down there and spent some time with him in his living room. We just sat there and just talked about life, about school, about what we wanted to do, what were our expectations. He was just kind of like, you know, ‘I’m a friend. I am here to help you if you need any help’.”

King said he knew Ed was tight with Webber and Rose, but it wouldn’t be until years later that he realized just how close they were. King learned quickly that Ed was genuine in whatever he did or said. “He did it for kids,” King said. “And that is why everybody I know, including myself, held him to a different standard. That was from his heart. That’s who he was.

“In the first encounter we were just like OK, you know, this home is open to us if we ever need it, if we got caught in a bind or just need to talk, anything. He was there for us. That was it. Then I would see him occasionally at a game or around, or he would come see us. He wouldn’t give a call, he would just show up. He’d say, ‘I came to check on you. Are you alright?’ That was it. ‘Is everything cool? Are they treating you right?’

“I am still stuck on how people could say that he somehow took advantage of players. I do not understand how people can draw that conclusion about someone that helps all kids. And that’s exactly who Ed was, a person who cared about kids. He did not look for kids’ involvement to benefit him and the university he was aligned with. That’s what real boosters do. They help their school or a particular program.

“When people say Ed was a booster, they’re wrong. He helped everybody. A booster is only going to help a player if it benefits him and his university. It was not like that with Ed,” King said. “He wanted to see if we were OK because he understood that we were in situations where we were at this major university and we could not use it. We were at this major university and we couldn’t get around.

“The only thing I would like to emphasize is something most people who are not close don’t understand,” he said. “Ed had one of the purest hearts of anyone you will ever want to meet. He was a genuinely good guy. You know, people who got an angle, they always trying to get something out of you. That wasn’t Ed at all. And that is something that I think people need to know, if they don’t know.”

King estimates Ed gave him no more than a total of two hundred dollars during his Fab Five career. King, who left Michigan after his junior season, said he never saw Ed dole out huge sums or exorbitant gifts to Webber or Rose, either, though he acknowledges that they could have been compensated without his knowledge.

“I know what the level was with me,” King said. “With me, Ed’s conversation was, ‘Are you are all right?’ And I had my pride, so I would always tell him, ‘Yeah, I’m cool.’ But he really knew I wasn’t cool. He’d just be like, ‘You know what? Don’t even… this is for you. I know the situation that you’re in.’ He was real like that. He talked to my parents. My parents talked to him. We got to know him.”

As he looked back, King sounded almost regretful that he and his teammates didn’t get more of a chance to cash in.

“At Michigan, I am sure boosters exist,” he said. “I know they exist. But I did not have any. That was why me and some of my teammates were pooling our money together. We were looking around like, ‘We’re just kind of out here.’ That is what it was. I found out later that players from other universities seemed to be getting treated well except for us. North Carolina, Kansas, Kentucky. You know how it is in our basketball fraternity, right? The stories they used to tell me….

“I’m not shocked, because I know. But they used to laugh at me talking about how we’d get in trouble for accepting gifts. ‘Get in trouble? What?’ So it was known while we (the Fab Five) were there that we were under a microscope, a big microscope. And the school left us out there. So for people to talk bad about Ed is crazy. He was trying to help, not hurt anybody. And when you’re hungry and broke and watching everybody else make money off you but you, I don’t think it’s wrong for a kid to get help. I think that’s only fair.”

♦ ♦ ♦

These recollections are indelible for those who were directly involved in these events. Perhaps that shouldn’t be surprising because some of these happenings were far out of the ordinary.

My father recalled the time a few of his young, street-toughened associates in the numbers rackets contacted him with a proposition that they handle some business regarding Chris Webber.

As his NBA career began to blossom, Webber would make frequent trips back to Detroit whenever his schedule permitted. These visits were ostensibly to see parents and family, but his motivation was primarily to hang out with his boys and bask in public adulation as The Returning Hero.

On one visit, a big bash was held at the State Theatre downtown for Webber and other pro players with Detroit pedigrees. It was billed as something like the “Return of the Big Ballers.” It was an almost instant sellout. I was definitely going to attend, because I knew some of the promoters staging the event, and because it had become the talk of the town.

With all that hoopla, Ed eventually heard about it, too. So did some of his younger business associates who liked my father and had made considerable money working for him. Now they were willing to go to the wall on his behalf.

According to my father, one of them said, “Hey, Ed. Chris is in town. At least for one night, we know where he’s going to be, and he’s got to enter and leave the theater.”

“I think I know where you’re going with this,” Ed replied, “but what’s your point?”

“Well, has he paid you back yet?”

“No, he hasn’t come correct yet.”

“We didn’t think so. Why don’t we go down there and talk to

him? Real personal-like.”

Suddenly Ed realized what they were asking. They wanted to confront Webber outside the State Theatre and let him know it would be in his best interest to repay Ed as he had promised.

Now, they respected Ed; they wouldn’t have taken Webber out on his behalf, but they definitely would have left their mark. One even suggested damaging a knee (or two) to put a crimp in his sky’s-the-limit young career.

Ed’s response was swift and sure. “I understand what you’re asking, and I appreciate the offer. I really do. But I have to say no.”

“Why not?” they protested.

“I can’t hurt those boys, I just can’t. They can hurt me, but I can’t hurt them. It’s not in me to do that.”

Chris Webber — and possibly a few other players who were indebted to Ed — had no idea how close they came to having total strangers run up on them and wreak vengeance in his name. I suspect, given Dad’s legendary generosity, some friends volunteered to do his debt collection as a freebie, knowing he probably would give them a share of whatever they recovered.

Yes, to Ed Martin’s mind, the Webbers had abused his generosity.

They had betrayed a cherished friendship. They had reneged on a solemn promise and failed to make good on a debt. Yet he could never cause or allow harm to come to them.

Somehow, despite his disappointments, he would not let himself become disillusioned. Deep in his heart, he believed that if he ever really needed assistance, his players would step up for him.

Beginning with Antoine Joubert, then so many others, even including Chris Webber and the Fab Five. Sure, if needed, they’ll be there for me. He could not know how soon and how severely that faith would be tested.

THE BOOSTER goes on sale Monday and will be launched in May at a series of special events and appearances by author Carl Martin. THE BOOSTER is published by Men for Others Books, whose primary mission is to selectively develop and publish books of particular interest to Detroit-area residents. Proceeds from sales of the first edition signed by the author support the Tarence Wheeler Foundation, which has been helping children in metro Detroit for 20 years. Copies of the 256-page, $29.95 book may be ordered directly at TheBooster.net.