The Roughneck’s Reckoning: Why Trace Adkins’ Silence Left Davos Trembling

DAVOS, SWITZERLAND — The World Economic Forum (WEF) is a summit accustomed to power. It is a gathering of the people who move markets, topple governments, and rewrite the rules of global trade. But on Friday night, during the summit’s exclusive Closing Gala, the assembled elite discovered that there is a distinct difference between “power” and “strength.”

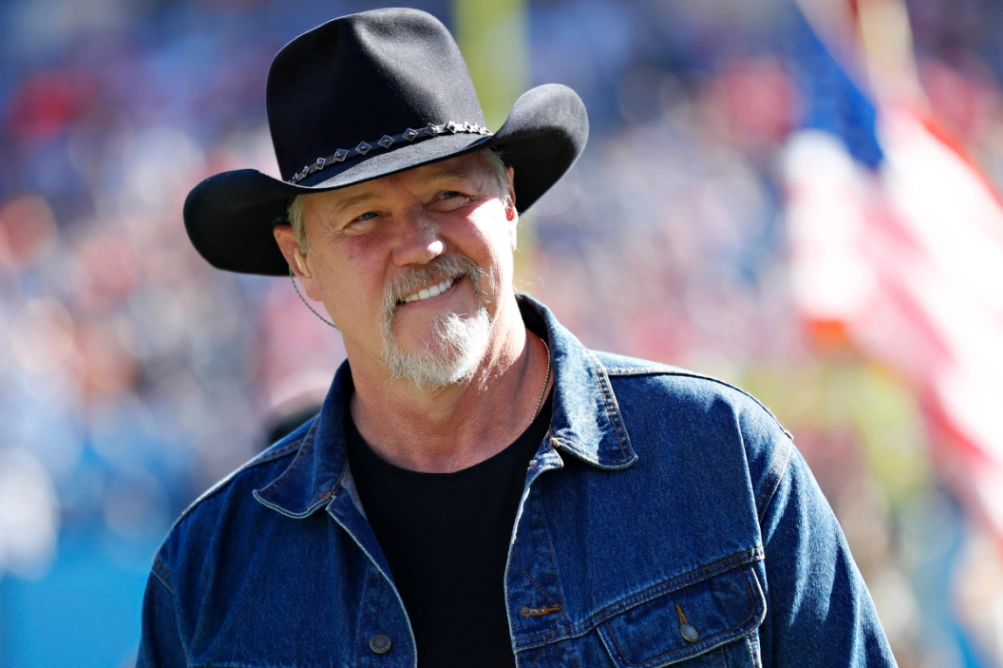

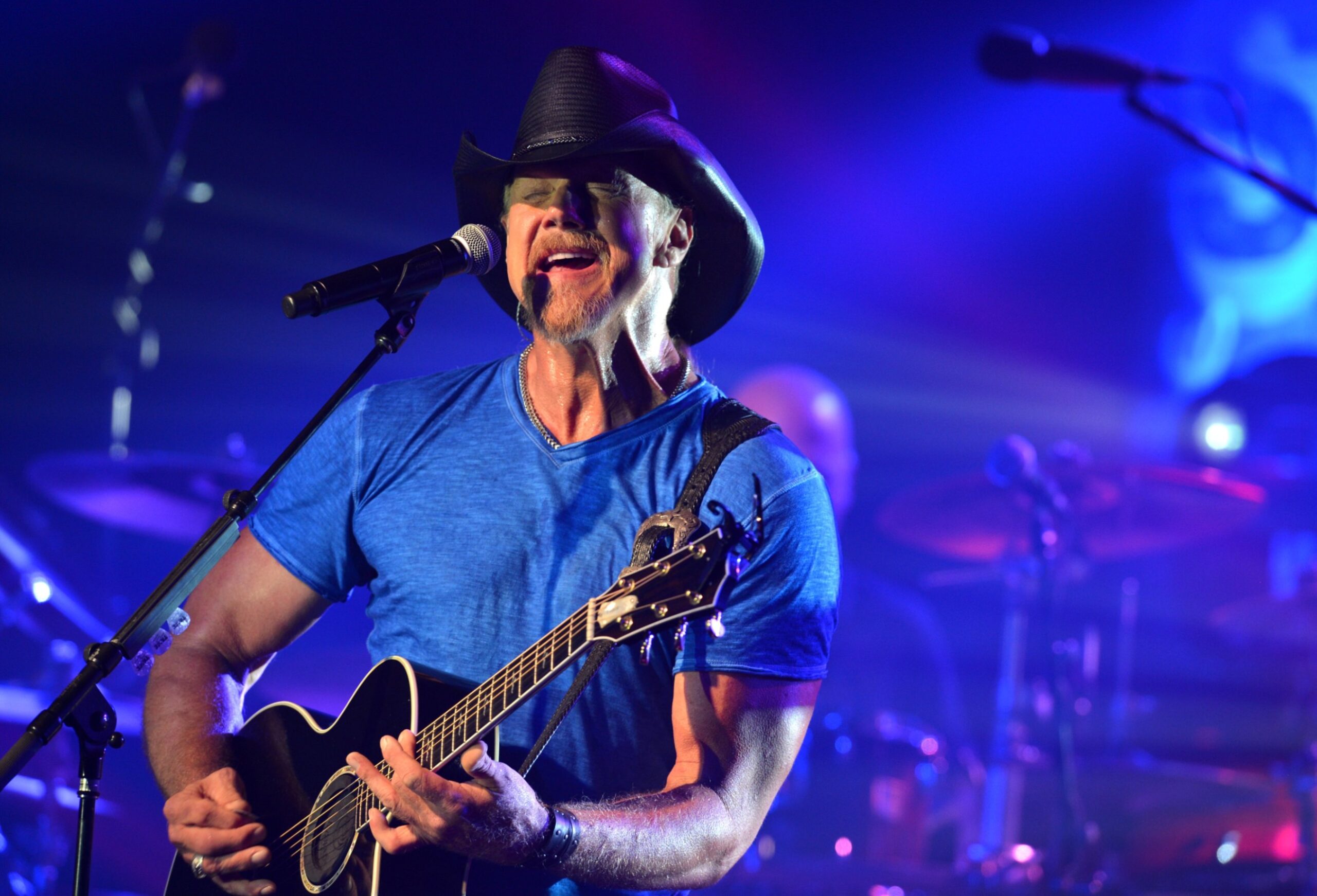

The organizers had intended for the evening to be a celebration of American resilience. To embody this, they hired Trace Adkins, the 6-foot-6 country music titan with a voice like a seismic tremor. Adkins, a former oil rig worker who survived a shooting and rose to become a member of the Grand Ole Opry, was the perfect casting choice—or so they thought. They expected a setlist of patriotic anthems like “Arlington” or sentimental ballads like “You’re Gonna Miss This.” They wanted the “Gentle Giant” to soothe their consciences with tales of heartland grit.

Instead, they got the Roughneck. And he didn’t come to sing; he came to settle a tab.

When Adkins emerged from the wings, the atmosphere in the Congress Centre shifted instantly. Dressed in a black leather duster and his signature black cowboy hat pulled low over his eyes, he didn’t walk so much as loom. He moved with the heavy, deliberate gait of a man who has spent years on offshore platforms, battling elements far more dangerous than a shareholder meeting.

The backing band, polished and professional, launched into the gentle acoustic opening of a heartfelt ballad. The audience of 300—comprising fossil fuel CEOs, tech moguls, and G7 leaders—raised their wine glasses, prepared for a moment of comfortable nostalgia.

Adkins didn’t lift the microphone. He didn’t smile. He simply leaned forward, his face shadowed by the brim of his hat, and growled a single command: “Kill it.”

The band stopped as if the power had been cut. The silence that followed was heavy, suffocating, and terrified.

“You folks wanted the cowboy tonight,” Adkins rumbled. His voice, a famous basso profondo, seemed to vibrate through the floorboards, bypassing the ears and hitting the chest directly. “You wanted the roughneck. You wanted a little piece of the heartland to make you feel like you’re still connected to the dirt.”

He gripped the microphone stand with a hand the size of a shovel, scanning the front tables where the energy barons sat in bespoke Italian suits.

“But I’m looking at this room,” he said, “and I don’t see anyone who knows the value of dirt.”

This was the moment the room realized their mistake. Adkins is not just a singer; he is a former pipe-fitter and derrick hand. He isn’t an environmentalist outsider criticizing the energy industry; he is an insider who knows exactly what it costs to pull power from the earth.

“I worked the rigs before I ever sang a note,” Adkins told the frozen room, his voice dropping to a register that felt like judgment day. “I know what it smells like to pull crude out of the ground. I know the cost of energy. I’ve got the scars on my body to prove it.”

He pointed a finger at the crowd—a gesture that felt like an accusation. “But we did it to keep the lights on for working families. You? You’re doing it to keep the score up.”

The critique was devastating because it stripped the CEOs of their “essential service” narrative. Adkins argued that the industry had moved from utility to gluttony.

“You want me to sing ‘You’re Gonna Miss This’?” he asked, referencing his 2008 chart-topper about the fleeting nature of time. “That’s a song about watching your kids grow up. But the way you’re running things, these kids ain’t gonna have a world to grow up in. They are gonna miss this. Because you’re selling it off piece by piece.”

Adkins then pivoted to his patriotic roots, delivering a blow that left the room gasping. “I love this land. I’ve sung about soldiers dying for every inch of it,” he said, alluding to his reverence for the military. “So let me be clear: I ain’t gonna sing a pretty song for the men who are poisoning the very ground those boys died to protect.”

He stood up to his full height, adjusting his hat with a sharp, final movement. “The land is tapped out, hoss. She’s tired. And you’re sitting here drinking the expensive stuff while the well runs dry.”

Stepping back from the microphone, Adkins offered no theatrical bow. “When you start acting like you give a damn about something other than your stock price,” he growled, “then maybe I’ll sing for you.”

He turned and walked offstage, his boots thudding heavily against the wood, leaving a vacuum of silence so profound that when a flustered dignitary knocked over a wine glass, the shatter sounded like a gunshot. The dark liquid spread across the white tablecloth like an oil slick—a poetic, accidental punctuation to the evening.

By Saturday morning, the footage had ignited the internet. In conservative circles and heartland communities, Adkins’ stance resonated deeply. He hadn’t used the language of the “woke” left; he had used the language of the working man. He framed conservation not as a liberal agenda, but as a matter of respect—respect for the land, for the work, and for the future.

Trace Adkins went to Davos as an entertainer, but he left as a giant. In refusing to lend his voice to the powerful, he amplified the silence of the land itself. The message was clear: The Roughneck has left the rig, and he’s not coming back until the bosses clean up the spill.