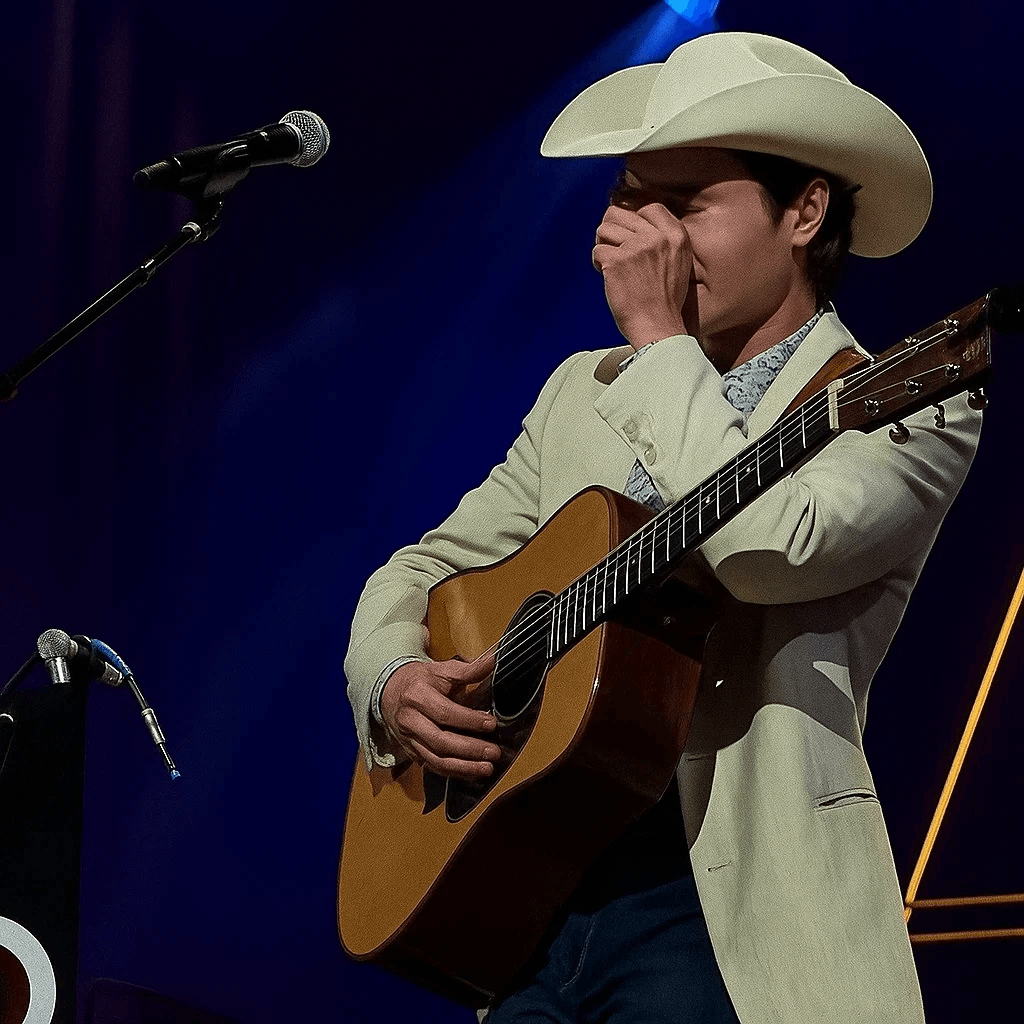

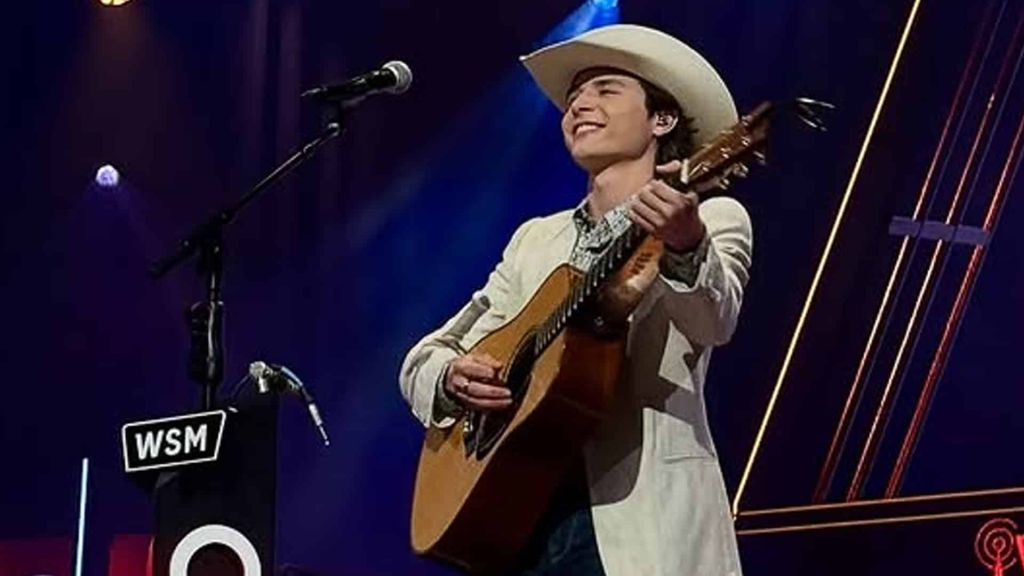

On a quiet night at the Grand Ole Opry, the lights dimmed, the chatter softened, and for a fleeting moment, time seemed to stop. There was no announcement, no fanfare, no scheduled performance. A man simply walked onto the stage, carrying nothing but his grief and a guitar. His name was John Foster. His purpose was not fame, nor applause, nor career. He had come for her—Maggie Dunn.

“It would have been your birthday today,” he whispered, voice trembling but clear. “I still hear you, Maggie.”

The room shifted. Some in the audience didn’t know who he was. Some wondered whether it was part of the evening’s program. But as Foster’s fingers brushed the strings and his voice broke into the first line of “Tell That Angel I Love Her,” the Opry transformed. This was not a performance. This was a vigil. A conversation between the living and the dead. A love song sung across decades of silence.

To understand why the room fell silent, you have to know the story. Maggie Dunn was not a starlet, not a Nashville celebrity, not a name etched in the annals of country music. She was simply Maggie—John’s first great love. She had been gone since the days when Blake Shelton was still a teenager, since the days when country music was shifting from honky-tonk grit to arena spectacle.

Maggie’s death was sudden, brutal in its finality. One minute she was there, laughing with John, sketching dreams of a future, making plans like all young couples do. The next, she was a memory. For Foster, her absence was not just grief—it was a rupture in time. The boy who loved her had to grow into a man without her. Every achievement, every heartbreak, every chord struck on a guitar carried her ghost.

And so he wrote. He wrote because he couldn’t speak. He wrote because the act of shaping words into melody was the only way he could keep Maggie alive. Among those songs was “Tell That Angel I Love Her,” a piece so raw, so heavy with sorrow, that for years Foster refused to perform it.

“It was hers,” he once said in an interview. “I wrote it, but it never felt like mine to sing.”

The Grand Ole Opry has seen everything—legends rising, legends falling, drunken mistakes, unexpected triumphs. But on that night, what happened wasn’t history in the traditional sense. It was something far quieter, yet far more permanent.

Foster walked onto that stage alone. No band behind him. No microphone checks. No prelude. He carried his guitar like a burden, like a memory too heavy to set down.

The crowd hushed as soon as he began. His voice cracked on the opening verse, but he pressed on. Each lyric trembled with the weight of decades of silence. Each chord felt like it had been pulled from scar tissue.

This was not the polished performance of a career artist. This was a man reaching back across time, speaking into the void, hoping his words might find their way to Maggie. For a few minutes, the Opry was not an auditorium—it was a bridge between here and there.

People in the audience later described the atmosphere as “holy.” One woman said it felt like “watching someone open a wound and let the whole world see it bleed.” Another man whispered to his wife, “That’s love. That’s what it looks like when love never dies.”

“Tell That Angel I Love Her” is not a chart-topping country hit. It was never released on radio, never climbed Billboard rankings, never earned Foster accolades. It remained hidden, played only in private moments, like a letter folded and unfolded a thousand times but never mailed.

The lyrics are simple—almost deceptively so. But behind their simplicity lies devastation. The song speaks not of closure but of continuation: the idea that love does not end when a life ends. That somewhere, somehow, the beloved still listens.

For years, Foster introduced the piece as “the song I wrote but could never sing.” He would strum a few chords, stop, shake his head, and set it aside. Audiences rarely heard it. Even his closest friends knew it only in fragments.

That’s what made the Opry moment unforgettable. It wasn’t planned. It wasn’t expected. It was as though the calendar itself—the fact that it was Maggie’s birthday—forced his hand.

As the final notes of the song lingered in the rafters, something unexplainable happened. The audience didn’t clap at first. They didn’t cheer. They didn’t rise for an ovation. They simply sat in silence, holding the moment, absorbing the ache.

In that silence, you could feel Maggie. Not literally, perhaps, but spiritually—woven into the chords, stitched into the tremor of John’s voice, echoing in the heavy air.

Eventually, applause did come. Slow at first, then swelling into something thunderous. But by then, Foster had already left the stage. He wasn’t there for recognition. He wasn’t there to be remembered. He was there to remember her.

In the world of country music, grief is no stranger. Songs of loss, heartbreak, and longing are the lifeblood of the genre. But Foster’s Opry performance was different. It wasn’t an act of artistry. It was an act of survival.

It reminded everyone watching that grief is not a chapter we close—it is a companion we carry. Decades later, Foster’s love for Maggie had not dimmed. It had not been replaced, not been rewritten. Instead, it had deepened into something almost sacred.

For young couples in the audience, it was a warning: love is fragile, time is cruel, and nothing is guaranteed. For older listeners, it was a mirror: the memory of their own losses, their own Maggies. And for Foster, it was both a goodbye and a hello.

The Opry moment has since become folklore. No official video was released. No recording circulated. The only evidence of it lives in the memories of those who were there. And maybe that’s the point.

Not everything sacred belongs on Spotify. Not every story is meant to be commodified. Sometimes, music exists not for the world but for one person. On that night, the person was Maggie.

But in hearing him sing, the audience became witnesses. They were invited—just for a few minutes—into the private heartbreak of a man who refused to let memory die.

As Foster placed his guitar back on its stand and walked offstage, the words lingered: “Tell that angel I love her.”

They were not lyrics. They were not poetry. They were a message. A message sent across years, across silence, across the chasm that death had carved.

And in that moment, maybe—just maybe—Maggie heard him.

When people left the Opry that night, they carried something intangible with them. Some carried tears. Some carried questions about their own lost loves. Some carried inspiration to call someone they hadn’t spoken to in years.

But all carried Maggie.

Because in the end, this was not just John Foster’s story. It was a reminder to us all: the people we lose are never truly gone. They linger in our songs, in our silences, in the way our voices tremble when we speak their names.

On what should have been her birthday, Maggie Dunn lived again. Not in flesh, not in presence, but in music. And as long as someone remembers that night, she will never be gone.