In the podcast Whistleblower, which released its first episode on August 27, journalist Tim Livingston takes on a major sports scandal that has mostly been swept under the rug with a mix of savvy PR and media incentives. In 2007, former NBA referee Tim Donaghy was arrested for betting on hundreds of games, including several that he refereed himself. Donaghy was convicted and sentenced to 16 months in jail, but to this day maintains that he never fixed any games by making bogus calls; rather, he used his knowledge of the NBA as more of a league of entertainment than true competition to predict which teams would win. Referees have favorite teams and favorite players—they’re more likely to make the right (or wrong) call when it benefits their pals, or less likely to harp on a star player that the league depends on.

But in 2012, five years after the scandal came to light, Livingston wrote a piece where he raised many questions about the matter, including Donaghy’s own claims. To him, it felt like no one had properly investigated the wider implications of referee culture in the NBA, the NBA’s own complicity as an institution, and the FBI’s perspective on Donaghy’s activities. In Whistleblower, which has essentially been in the making for the last five years, Livingston interviews basketball players like Rasheed Wallace, members of the mafia, the FBI, as well as Donaghy himself to make sense of a saga that has never been fully brought to life. In the two episodes I had access to, Livingston is an affable interviewer and committed basketball fan, but also an intrepid journalist, a curious and dogged seeker. His orientation toward his subjects is both open and skeptical, and by maintaining this balance, he is able to make startling and revealing discoveries about the true nature of the corporate systems that reign supreme, in the game and in life.

Whistleblower is a series for sports fans, true crime junkies, and truth seekers. I spoke to Tim Livingston about the podcast and how he approached the series, building strong relationships with high-profile sources as a freelance journalist with no official ties to the league.

In the first few episodes, you’re trying to sort out how NBA game-fixing, by referees, can actually consist of using technically proficient forms of reffing that just aren’t enforced in the NBA because the NBA is primarily about entertainment and not—as the fallen former NBA ref Tim Donaghy himself claims—athletics. How do you make sense of that claim and how did you drill into this story based on this idea that maybe fixing doesn’t look like what we think it would look like in a league like the NBA?

Tim Livingston: Where I’ll start is, NBA refereeing is incredibly subjective. If you watch basketball, if you play basketball, if you know basketball, you understand that concept—that what constitutes a foul is a lot different for one ref than another ref. And the big fundamental problem with basketball as a game, as a sport, is that the referees have a ton of power when it comes to enforcing the rules—there are different rules for different players, there are different rules for different teams. There’s very little congruity in the rules. That’s the fundamental problem that affects the NBA during the Donaghy scandal and that affects the NBA today. Go on Twitter for any of the NBA playoff games over the coming weeks, and you will see fans bitching ardently about foul calls. It is inevitable, it will always plague the game.

As far as the NBA scandal goes, we’re tasked as basketball fans with a very difficult problem to solve. It’s what constitutes a foul, right? That’s where we’re starting off this podcast, and I think what you want to get to the root of. With Donaghy specifically, he was a very highly rated ref; according to the NBA referee grading system, Tim Donaghy was a superlative referee. So with that being said, what does that mean? That if this guy was a fantastic ref and there’s serious questions about the legitimacy of hundreds of games that he refereed, then where does that leave us?

In both entertainment and sports journalism, there can be an incentive to look at things from the establishment perspective. With Whistleblower, you’re running counter to that incentive—rather than seeing the NBA or even the FBI as these all-knowing authorities who offer the final word, you really dig into their claims and question their perspectives as organizations. Did you ever fear a little bit for your career or does the current lack of significant access in sports journalism make it easier for you to jump into a story like this?

That’s a great question. There are really powerful people behind the scenes, but they’re a little scary. In 2012, when I wrote the original article about Donaghy, I was a freelance writer. I was writing purely about sports, but I didn’t have any affiliation with the NBA; I wasn’t covering a team. There’s nothing stopping me from writing critically about the NBA. If you look at the scandal, when it broke, the powers that be at the NBA were absolutely brilliant when it came to the media and PR in general. They were brilliant PR strategists.

So they often were able to get their story out the way they wanted to get it out. And they were also able to squash the negative stories that could damage the brand. So when this story erupted, what I found interesting—because I wrote that piece five years after the scandal—is that nobody had taken the other side, which is being critical about the institution, about the NBA. And I think that happened because NBA sports journalists—the people best equipped to talk with sources within the league and expose something to the story—their jobs, their livelihoods were dependent on the NBA existing. This story goes so deep and there are so many layers to this and it gets really, really ugly. I think people have always known that—I really do. And that’s why the media’s role in this is an interesting one, because if you love the NBA, you love basketball and this terrible thing happened, you might want to write about it, but you also want to put food on the table. You also want a job. You also want the sport that you love to exist. And this was so bad that if everything really came out in one tidal wave back in 2007, the NBA might’ve been in trouble. It’s that dark.

“I mean, we’re talking about the mafia, we’re talking about the NBA, which is an incredibly powerful organization. I’ve had a lot of bumps in this road—and there’s definitely been points where I wanted to stop.”

And with me personally, I mean, we’re talking about the mafia, we’re talking about the NBA, which is an incredibly powerful organization. I’ve had a lot of bumps in this road—and there’s definitely been points where I wanted to stop. And I’ve been scared and worried about the ramifications of exposing this. Ultimately, obviously, I haven’t stopped, but there have been numerous times in the last eight years where I’ve said, This is scary. This is too much. I shouldn’t go here. Whether those fears are valid or not, I don’t know, but I’ve felt those emotions numerous times. I have therapy bills to prove it, and that’s a real thing because this is a very, very dark world. That being said, Cassie, what I think is interesting is that the NBA right now is in a great place. 2020 is a lot different than 2012, and it’s a lot different than 2007. And my hope is that by this finally coming to light now, I think a lot of people are more willing to talk about it than they would’ve been 13 years ago. Additionally, they were probably still employed by the NBA, which issued a gag order across the entire league when the story came out. So I think time has healed a lot. The NBA is going to be absolutely fine, and we want the NBA to be fine. We just wanna understand the truth about this scandal and the truth about the system and the culture that existed at that time, because it’s a fascinating one. And it’s a story that I think needs to be told.

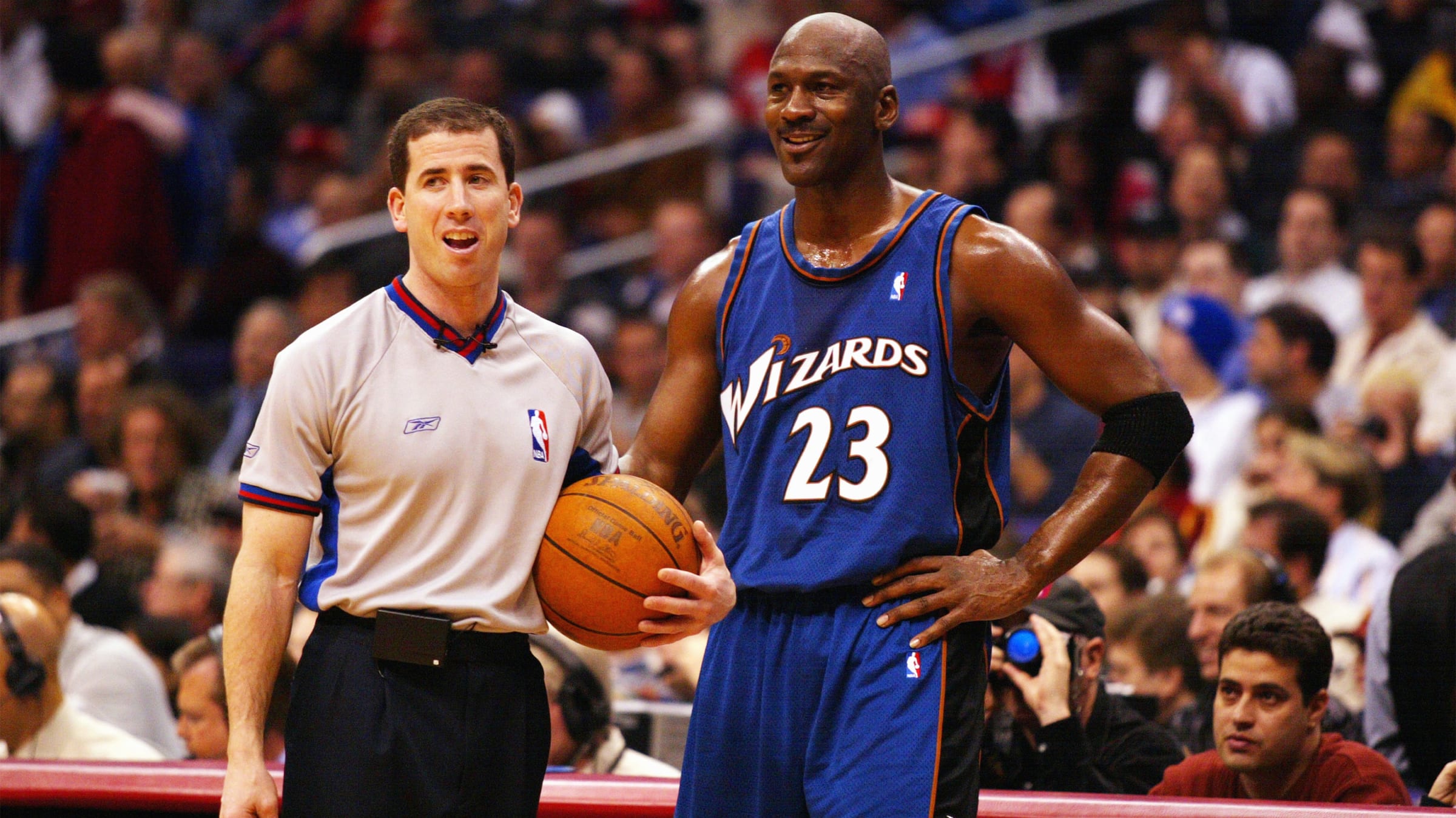

I wonder what the juxtaposition of Whistleblower is with The Last Dance, an NBA-focused documentary where there’s so much access and approval within the system.

I kind of consider this the dark Last Dance podcast. I loved The Last Dance, I think [director] Jason Hehir is a fabulous filmmaker. And, to your point, I think the great thing about The Last Dance was the access, and really getting to understand these characters in a way that we never have been able to. As a journalist, the fact that Michael [Jordan] had essentially complete control over the final product, do I love that part? No. But essentially the story was incredible and the journey was incredible, and you got that because, you know, we’re fascinated by these characters and we got to see them in a way that we never have before. And my hope is with Whistleblower, there’s a very similar thing, it’s just, instead of the last championship of the greatest team ever assembled it’s the crumbling of a very corrupt refereeing system.

One part that I really liked was when you had a meeting with Tim Donaghy and he’s talking about all the scandals with these refs and you say, “Oh God, I think I’m friends with this guy now.” And then you’re kind of worried because you’re like, well, what’s the story going to be like? I don’t even know if this kind of relationship can hold. And I felt like that gave such important insight into what it actually is to do reporting.

I’m really attracted to characters, so I have a podcast I co-created with Gilbert Arenas, and Gilbert Arenas says some things that I disagree with, put it that way, but ultimately he’s unfiltered and he’s a character. And that made me think that he was interesting, somebody who could be good to potentially work with.

But I’ve spent the last five years really getting to know a lot of players and coaches and it’s been an interesting journey. But those relationships allowed me to add a lot of depth to this podcast because arguably the most controversial are Rasheed Wallace, who’s the first NBA voice you hear. When you think of a player sparring with the referees, that’s the guy that I knew I needed to get to this podcast. And he also got into an altercation with Tim Donaghy that got him fined 7 games, $1.2 million. So I feel that again, the timing of this is, I need it to happen for me personally in 2020. And we’ve gotten all of our in-person interviews [done] right before COVID-19. So the timing of this is all pretty surreal.

There’s a huge sports audience that’s going to be interested in this type of story, but you also take a lot of pains in the podcast, so far at least, to make sure that it’s legible to people who maybe don’t really follow sports as closely. Was it your intention to make it more available to a wider audience?

It was absolutely our intention to make all of the complex sport concepts easily digestible for a widespread audience, because we said at the beginning of the podcast, and it’s true, that this is a sports scandal, but it’s really a corporate corruption scandal. It’s a scandal about money and about power and about all the things that any human can relate to. You don’t have to be basketball fans to get immersed in this world as a story.