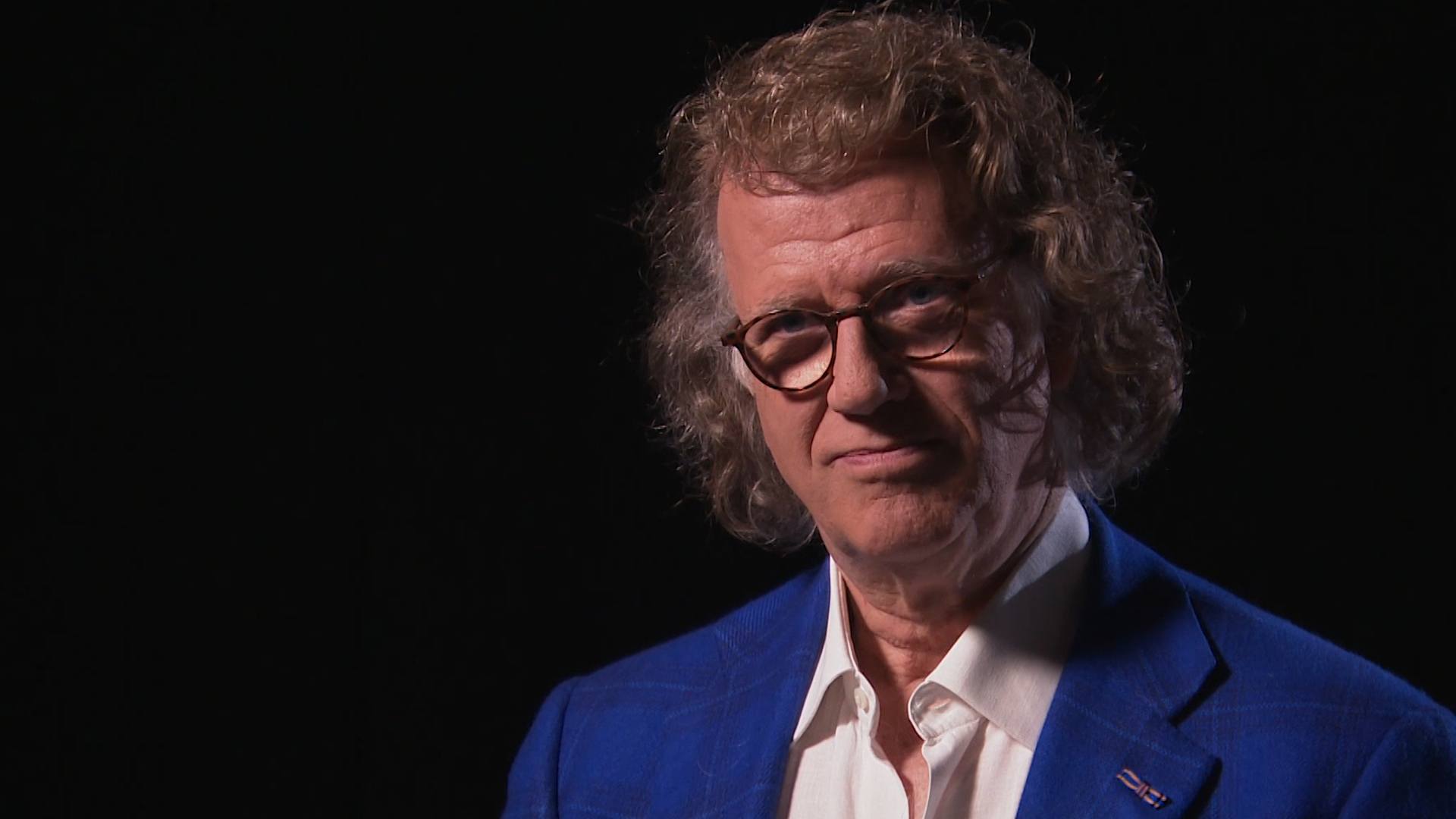

André Rieu’s Journey: From King of the Waltz to Vulnerable Maestro!

Everything changed after André Rieu, the king of the waltz, collapsed mid-performance at the age of 75, bringing the world of music to its lowest point.

But at the height of his genius, what caused that collapse?

We must be aware of the specific events in his life to comprehend.

André Rieu was born on October 1, 1949, into a family during a period when punishment was valued more highly than a child’s mental health.

He was the third of six children to a father who commanded the home with the same ruthlessness that he did on stage.

Orchestras admired his father, who was also a well-known conductor.

However, children at his home dreaded him.

Their house was devoid of laughter and lullabies.

Love was frigid and abstract.

André would later add, “My parents didn’t love me,” not as a wound dug up, but as a silent admission of reality.

His mother had an obsession with abilities and academics.

Imagination, in her opinion, was a liability.

When a teacher complimented his artistic abilities, it echoed back at him through the house like an indictment.

The urge to be creative was a weakness, not a strength.

However, everything changed when he became five years old.

A slim, elegant 18-year-old became his first violin instructor.

She did not chastise him; she encouraged him to feel.

Young André discovered something he had never heard of in the sweep of her bow: freedom.

He was certainly amazed.

He then turned to music, which was a very enticing sensation.

It wasn’t a win; it was something that would emerge from deep within him.

Scales were practiced by other kids, but he sought resonance.

However, happiness had a price.

His developing love of waltzes during his adolescence ran counter to his father’s austerity.

His father’s lyricism was derided at home.

He heard his father yell at him, “I didn’t raise you to play waltzes.”

Those were not merely reprimands; they were meant to destroy his soul.

When Marjorie showed up about 1968, that was the last nail in his coffin.

Not a conductor’s score, but André’s chosen companion.

His mother greeted her angrily: “Leave,” she commanded.

It was rejection after rejection.

André left that very evening.

He didn’t go back.

As he became famous, their house stayed the same—a vacant shell.

His parents never once went to his shows.

Even though the arena was crowded with devoted supporters, he couldn’t get rid of the recollection of the quiet at home.

“I spent years in therapy trying to understand why my childhood felt so hollow,” he once admitted.

That gap was never filled by the applause.

But he felt seen at last through music.

“The violin was more than just a musical instrument; it served as a lifeline. Windows opened whenever he played.”

André broke and began the rebellion in 1978 following years of formal orchestral testing and enduring the sterile echo of concert halls.

He founded the Maastricht Salon Orchestra.

Twelve dreamers full of optimism and without any costumes.

These youthful aspirations were performed in forgotten border towns, backyard weddings, and small community halls.

They were merely doing music for its own sake—just sound shared and human.

No critics, no elaborate sets.

There was another person at the center of everything: Marjorie.

She managed business meetings, bookings, and ghostwriting arrangements, and was steady, accurate, and invisible.

The unseen power underlying his apparent sorcery was her.

She joked, “Sell more records,” not out of curiosity or interest, but to create the future when he paused at the thought of purchasing a dilapidated castle.

This silent revolution was not broadcast on television.

He officially established the Johann Strauss Orchestra in 1987.

Twelve artists, but a bold goal to bring back the soul of music.

The solemn formality was abandoned.

Inviting joy, they donned color instead of black tailcoats.

They had an electrifying 1988 New Year’s Day launch, complete with dancing lights and melodies of laughter.

Audiences roared, but critics scoffed at them.

It wasn’t a concert they were at; music was being reclaimed.

By 1995, a spontaneous change occurred on one of the biggest platforms in Europe, the UEFA Champions League final in Vienna.

As Shostakovich’s Waltz No.2 ascended, Rieu and his orchestra strode onto the field.

Football supporters clapped, moved, and swayed.

The stadium was a graceful glow, and tension melted away.

The timing felt cosmic when Ajax scored.

The incident turned into a legend.

“Strauss and Company” quickly rose to the top of the Netherlands charts for 19 weeks.

It was unprecedented in the world of classical music.

Millions of copies were sold worldwide.

Australia immediately followed.

More than 38,000 spectators crammed into stadium seats in Melbourne to watch a live fairy tale.

They also owned eight of the top 10 DVDs in the nation.

Every one of them was his.

He was standing next to music stars like AC/DC and Pink.

Even with all of that accomplishment, some people still disapproved of what he was doing.

The traditionalists were the ones who shrank back.

But to Rieu’s audiences, it meant everything.

One conductor said, “Musical pornography,” mocking lights and gowns, sneering that joy had no place in art.

The grandparents’ emotional tears had found a stage in the dancing family.

“You don’t feel the solemn hush that drives people away,” he remarked.

He meant it.

Concerts were not what he was selling; he was giving the populace hope.

However, the maestro was inconsolable behind the glittering lights and packed stadiums.

At the height of his success in 2010, a new issue emerged.

André developed an inner ear infection due to a viral illness.

Balance is crucial for a violinist.

His entire world swung.

Tours were canceled.

Shows were canceled.

It was more than just sickness that made the man whose main selling point was “can do” have to confess, “I can’t.”

He had been unaware that he had a fracture.

It was more than just illness, to be exact.

It was the instant a myth broke, exposing itself in a distorted mirror and a shuddering unbalance.

André Rieu faced a critical moment in 2010 at the age of 62 due to a vestibular nerve virus infection.

He was thrown into unrelenting pandemonium by an attack on his inner ear.

Nothing provided support—not even the floor underneath him as the room swung around.

His hazy eyes scanned the walls that whirled with ruthless velocity as he lay bedridden.

Now the man who had never faltered felt a drift.

Doctors prescribed rest.

Once as stiff as a cement wall, the man in the tour schedule fell apart like cheap sheet music.

André took a long time to recuperate.

Every kind of traditional treatment was unsuccessful.

Then an Australian fan wrote a letter.

He gave vestibular exercises that helped him regain his balance and talked about his personal struggle with the same virus.

Desperate, André took the advice.

The distortion gradually stopped.

He stood up again after withdrawing for months.

Unsteadily at first, then firmly.

He eventually made a comeback to the stage and led a tour that signaled not just his musical return, but also his reputation’s revival.

Although everyone believed he had returned to his ideal self, no emotional or physical hurt truly heals without leaving a mark.

The dizziness subsided, but his balance was still precarious.

Although management was quick to reject the resurgence of imbalance concerns in 2012, they acknowledged that the ear that had been attacked was still vulnerable.

They also warned that he would be in serious risk, particularly if he was performing if there was a potential that his illness may return.

Then came a December tour in Leeds in 2016.

Once more, the horn of dread blew.

André held a special place in his heart for a companion.

He was a long-standing buddy and trombonist named Rude Merks, and he always went with the group.

The fact that he had passed away while sleeping was shocking, but everyone else was going about their own business.

André’s world was rocked by a massive earthquake.

He conducted the Nottingham show in the middle of the tour without blinking, and he stopped the others in Glasgow, Birmingham, and London.

This was not sickness.

It was sorrow, heartbreaking, and irrevocable.

Later on, he acknowledged that he was like a brother—a family in every manner.

The orchestra swayed in grief.

The weight of what had disappeared from André’s life was there when the music performances came back.

Despite everything, he remained resilient, and he took the stage in 2019 when a terrible sickness hit him, causing him to tremble and sweat.

Those who knew him saw how he was struggling with that on stage.

Yet the smile persisted.

Then came the moment that would shatter him.

He had to place six sold-out shows in Mexico City in March 2024.

The triumph seemed promising.

Acuity became crisis after only the second performance.

Like storm clouds, sickness, travel lag, and altitude came together.

According to rumors, he faltered backstage—fever, disorientation, and dyspnea.

Touching his phone, he whispered a call to Marjorie: “This is not how I want my first concert day to go.”

That was how four concerts ended.

More than 40,000 ticket buyers were incensed.

All 125 members of the orchestra were sent home in the middle of the tour.

Tickets were refunded and flights were reversed.

They had no way to maintain their peaceful dignity in the midst of emergency turmoil.

Something new occurred during that pause.

His son Pierre came forward.

He was no longer only a tour manager or a son; he turned into a shield.

No more marathons across continents.

The speed decreased.

Sleep recuperation.

Europe-only concerts and a gentle fortress centered on André’s well-being.

There was no retreat; it was the right decision.

However, they would have avoided the repercussions of what was going to happen next if it had been taken a little sooner.

Meanwhile, everything depended on Pierre, who had been in charge of logistics until taking on the role of curator of tempo.

Where André would have charged ahead, he put brakes in place.

Now, every flight and every location went through a screening.

“Is he capable of doing this without breaking?”

By taking on the role of weightbearer, he made it possible for André to recover his music without sacrificing himself.

Everything was changed by that collapse and that choice.

This was not a maestro’s downfall; a new one was being born.

Someone who knew you had to earn every note worth playing—care, not endurance.

And as a result, he became more memorable and human.

By the summer of 2024, the change was apparent.

However, some of the wounds were still open.

Slowing down had a hidden cost for 75-year-old André Rieu, who had made his livelihood on the road.

The steady motion had been his lifeblood for decades.

Every performance now carried a different type of pressure as Pierre tightened his grip.

The need to demonstrate that he was still capable, both for the public and for himself.

That July, he made a comeback to his hometown stage, MRI.

Every face in the crowd knew the man’s background, making it the safest arena on his calendar.

Like they had done for years, the show sold out right away.

However, the preparatory work behind the scenes had changed.

Rehearsal blocks included information about medical clearances, oxygen availability backstage, and rest periods.

His team, which now collaborates with doctors and physical therapists, used to concentrate on lighting signals and sound balance.

The checklist was attached to his dressing room wall, but the audience never saw it.

It was a subdued admission that his body was no longer his silent companion.

It was a short list, but it was accurate: hydrate before the performance, keep the encore brief, and avoid handshakes after the show until your heart rate has steadied.

Pierre applied these regulations with the same gravity his father had previously shown for tempo indications.

Nevertheless, there were times when the old pace attempted to prevail, despite the protections.

Lost in the surge of strings, he played a waltz longer than intended on the third night in Maastricht.

For a short while, it seemed like the past as the orchestra played and the audience stood.

However, his shirt stuck to him with the same wet weight he had experienced in Mexico City as he left the platform.

Pierre’s face conveyed what neither of them wanted to say out loud—they had almost gone over the remaining line.

The modifications were artistic as well as physical.

André started moving some of the pieces about, reducing the volume in ways that only a skilled ear could detect.

There were fewer high-energy pieces.

The set lists started to focus more on symphonic storytelling, slower waltzes, and ballads.

Unaware that the modification was actually a tactic, fans welcomed it.

It was a method of creating the appearance of limitless endurance while using less energy to do it.

He spent more time at home in between gigs than he had in decades.

Maastricht used the lawn behind his 15th-century house and the stone streets as a rehearsal space.

He kept his energy bank full for performance days by practicing in privacy rather than spending hours with the entire orchestra.

Friends observed a fresh readiness to say no, fewer late-night calls, and a gentler rhythm to his voice.

The cheering was different when André Rieu returned to the stage following his protracted health fight.

It was more than a party; relief was felt.

The king of the waltz’s next performance was uncertain for months.

He was stopped in the middle of his tour by a viral ailment in 2009.

Despite doctors’ warnings that pushing too quickly could ruin his career, André never considered leaving the music industry.

Antwerp hosted the first concert back.

Prior to his illness, all of the tickets were sold out.

A smaller performance was anticipated by many.

Rather, Rieu performed for three hours straight without skipping a single song.

It was that same enthusiasm he used to greet his audience.

But the astute observer saw the shifts between pieces.

He sat.

For the first time in decades, his son Pierre was seated sidestage during the whole performance as he paced himself.

During his father’s illness, Pierre Rieu had been quietly managing a large portion of the company.

As you are aware, in addition to managing schedules and overseeing the production, he also decided whether or not the tour would continue.

He was clearly now a part of the safety net of the show.

André acknowledged in subsequent interviews that Pierre was strictly instructed to take over if he had symptoms of vertigo.

It was a big responsibility.

It was more than just music; this has to do with the health of his father.

Fans continued to discuss a memorable moment that happened halfway through the 2010 tour.

During the encore in Maastricht, André stopped and beckoned Pierre to the front of the stage.

Pierre reluctantly entered the spotlight to the clamor of the audience.

André gave him a microphone and invited him to join the orchestra in singing.

The audience didn’t care that Pierre wasn’t a professional vocalist.

For thousands of people to witness, it was a unique look into their intimate relationship.

The video, which revealed a side of André that was rarely shown in interviews, went viral online.

The father, not the maestro.

The pace was still brutal behind the scenes.

Careful planning was necessary for André’s recuperation, but touring demands left little time for relaxation.

It was quite hot in Brazil.

Jet lag in Australia was terrible.

The most physically taxing numbers were positioned early in the show when André’s energy was at its peak, according to set lists that were modified by his staff.

The danger was always there.

Even then, everything may end again if his condition returned.

During those years, Pierre’s job became even more significant.

He was doing more than just logistics.

He developed into a silent protector who occasionally overrode his father’s intuition.

André acknowledged that he occasionally disagreed with Pierre about slowing down, but he also understood that the tour could go on because of his son’s caution.

Subtle alterations in André’s performance style were noticed by fans.

There were additional opportunities for audience participation and storytelling pauses in between performances.

It was more than just energy conservation; André was deliberately trying to make his performances more personal.

His goal was for the audience to experience the adventure with him—all the triumphs, all the anxieties, all the highs.

The true machine returned in full force by 2012.

Once more, the trips crossed continents, but his illness’s shadow never completely disappeared.

In interviews, André talked candidly about how it had impacted him.

He no longer believed he was unbeatable.

Each performance felt like a present rather than a promise.

The return was astounding in terms of finances.

The excursions brought in millions of dollars.

Sales of DVDs increased.

The Maastricht concerts evolved into yearly international film festivals.

However, the success was the result of a never-ending balancing act between safeguarding the guy at the center of it all and providing the spectacular spectacle that fans had come to demand.

Pierre’s impact on corporate choices became much more apparent.

In order to give the orchestra more time to practice without feeling rushed, he worked with venues to extend setup periods.

No matter the venue, he demanded that medical personnel be on hand at every performance, and he started getting ready for something André didn’t talk about much.

What would happen if he was unable to tour on this scale anymore?

Those close to André noticed the signals, but he dismissed the concept of slowing down in interviews.

The distances between the excursions increased a little, but they were still enormous.

More time for recuperation was made possible by the calendar.

It was preservation, not retreat.

The demands persisted, though.

The calendar had more than 100 concerts in 2016.

Constant travel, shifting weather patterns, and the mental strain of conducting an orchestra in several different nations were all part of that.

Fans saw only the sparkle in the song.

When the lights went out, they failed to notice the fatigue.

Then, during a tour to Europe, the incident occurred.

It was serious but not dramatic enough to garner media attention.

André waited longer than normal in between numbers during a Vienna performance.

Pierre took a closer look at the stage.

The music went on, but the atmosphere changed.

André later said that during that set, he had felt lightheaded.

The memory remained with them both even after he ended the presentation.

It served as a warning that danger always existed, regardless of how cautious they were.

Without revealing the flaws to the public, it strengthened Pierre’s implicit duty to defend his father.

André reduced some of the show’s physical elements the next year.

He gave his orchestra members more responsibility.

He supported their individual performances, allowing himself brief breaks without interfering with the concert’s rhythm.

Fans adored it.

They interpreted it as kindness.

It was also a tactic for André.

However, the adjustments did not imply a retreat.

The Maastricht concerts broke attendance records in 2019 with thousands of people singing along.

André stood on the platform grinning and holding his bow.

It was an instance that might have marked the pinnacle of a career.

He wasn’t finished, though.

The trip halted overnight in 2020 when the epidemic struck.

It was the longest hiatus André had ever taken from performing as an adult.

He used it to record, practice, and maintain constant communication with his players.

However, it also turned into a period of introspection.

He got a glimpse of what life might be like without touring all the time during the forced pause.

He came back to the stage full of vigor after the constraints were removed.

The crowds had grown in size, volume, and emotion.

Live music had been missing.

André hadn’t acknowledged how much he’d missed them.

The trips have continued in recent years, but with lessons gained from the past.

The timetables are more intelligent.

The journey is designed to reduce stress.

Pierre attends nearly all of his performances, yet prepared yet observing.

André Rieu is 75 years old.

He continues to play with the same fervor that made him famous throughout the world.

However, people who are familiar with his past are aware of the significance of every note.

Each performance is a triumph over the sickness that threatened to keep him quiet.

There is one item, though, that André has kept private—a choice that might alter everything.

André and Pierre talked about the prospect of doing their biggest ever world tour in a recent private chat that was overheard by a team member.

There are no dates yet, although no information has been made public.

If it occurs, it will put everything they’ve constructed to the test: the link between father and son, the music, and the endurance.

For the first time since his return, the debate is whether André should do it rather than if he can.